This is an article sharing some things I’ve learned getting stuff done. The idea is to pass on techniques that I’ve found useful, and hopefully to get folks to share techniques they’ve found useful too. Let me know if you find it useful, and I’ll do more of them.

The mess

What had the hell had gone wrong? S was the project manager on a project for a new client at a company I used to work for. The project, to build a new phone system for a major travel-agent website, was supposed to take 10 weeks and cost about $100,000. The project was 1 month ahead of schedule, and was running about 25% below budget. Users loved the system. All measurements and metrics were heading in the right direction. Yet when I was assigned the account and checked in with my client, she was not happy. In fact, she’d begun to wonder had she made the right decision to choose us in the first place.

What had gone wrong? Simply, S didn’t use soap[1], and it was costing him his client!

Why doctors use SOAP

I look for concepts in other fields that might help me get better at getting stuff done. My wife is a doctor, and I often find myself looking at how doctors go about their jobs. And it turns out there are lots of parallels between being a manager and being a doctor. For example, let’s look at problem solving:

| Doctor |

Manager |

| New patients or symptoms pretty much every day. |

New challenges or problems pretty much every day. |

| A lot of (often conflicting) data for you to look at |

A lot of (often conflicting) data for you to look at |

| An expectation on the part of your patients, managers, and administrators that you should get stuff right |

An expectation on the part of your clients, managers, and teams that you should get stuff right |

| Often not much time to make decisions |

Often not much time to make decisions |

| If you make a mistake, your patient may die. |

Um… |

And suddenly the analogy breaks down.

The consequences of a doctor making the wrong decision far outweigh the consequences of most managers’ decisions. Given that, you’d think that doctors have figured out some pretty good general ways to approach solving problems.

And they have: They use SOAP.

What is SOAP?

The medical field has institutionalized a way to evaluate treatment for every patient; every doctor who is coming up with a treatment plan creates a SOAP Note. Its’ a very simple concept:

- S (Subjective): What subjective data can I glean about the patient. Does the patient say they feel depressed? Do they say they feel pain?

- O (Objective): What do my tests show me? Blood pressure? Heart rate? Reflexes? MRI Scans?

- A (Assessment): Using both the subjective and objective data, what is your assessment of what’s wrong.

- P (Plan): Now, what’s your plan to make things better.

Doctor’s force themselves to always look at subjective as well as objective data. They always explicitly assess the situation[2]. And they always form an explicit plan. Go ahead and ask any doctor you know – they all do this (well, almost all, and almost allways as my wife would say)!

Why? Well it’s because as humans we have an ingrained tendency to either be too objective or too subjective, and that usually leads to bad things.

If you only look at the objective data, you miss potential symptoms your tests couldn’t detect. You don’t find out that while a test shows a medicine is within tolerable ranges, the dose your patient has is making them throw up. If you only look at subjective data, you get patients claiming pain, but only trying to score free drugs. You need both to get a full picture of a problem before you assess and plan. By institutionalizing this simple framework, the medical community has been able to significantly decrease its error rate.

How we’re biased differs depending on who we are, and how far we are removed from the people involved. Some people tend to almost exclusively look at objective data[3], and don’t believe their peers if a spreadsheet says otherwise. Other people tend to almost exclusively look at subjective data and ignore numbers screaming to them at their face. I know you’ve met both extremes in your career.

Most people are somewhat in the middle, but will tend to look mostly at subjective data when the problem is emotionally close[4] and at mostly objective data when the problem is emotionally distant[5].

But to make the best decisions, we have to discipline ourselves to always look at objective and subjective data. The SOAP framework is an excellent way to do that. It doesn’t need to be very formal. Doctors just follow the convention when they write notes on a chart.

How did SOAP clean up this mess?

So, getting back to S. S had been trained (as most good managers and project managers are) to be on top of all his metrics. He watched his timeline like a hawk. He watched his budget like a hawk. He kept “feature creep” (the tendency of “new ideas” to sneak into projects and cause timelines to expand) to an absolute zero. He quickly assessed problems and made rational plans and decisions to keep everything running smoothly. He had the “O”, the “A” and the “P” down pat! But he didn’t take a look at any subjective measures – if the metrics were good, the project was good.

And this was costing him his client. You see, everything was going swimmingly, except S wasn’t asking his client’s opinion enough. His decisions were good, but his client would have preferred her team were actually consulted more about them. Not that they would have decided differently, but the client wanted her team to feel involved. And because her team didn’t feel involved, they were complaining about all sorts of little inconsequential things (like what format bug numbers should be reported in), because S had made a decision without asking them.

S and I sat down shortly after I got the account assigned (and poor S was forced to actually work for me) and I introduced him to SOAP. For about 4-weeks, I actually made him present problems to me in that framework. And S started looking for subjective measures. He talked to his client and asked her not just about the metrics, but about how she felt. What could be better? And she told him[6].

Within a week, S was actively changing his behavior and the client was happier. I got one of my favorite voice mails of all time: the message said “I don’t know what’s gotten into S, but be careful, or we might decide we want to hire him.” By making sure he looked at both subjective and objective data, in a somewhat structured manner, S was able to drastically improve how well he managed both the project and the client.

How do you get honest subjective data?

In a business context, people are often trained to only give negative feedback objectively, and often will mask their subjective opinions in order to either spare you emotional discomfort or to avoid confrontation. Guess what? We’re human! As a manager you need to expect this to happen, and not get frustrated when you can’t get feedback.

The best way to get real subjective data is to be open, always. That’s hard (and while I’m trying, I certainly don’t succeed at it).

But here are some techniques for getting good subjective (and negative) feedback that I’ve had some success with in the past:

- First, ask for it. So many people don’t. Just ask someone how they feel, and be genuinely interested in their responses. Then, and this is the important thing, make at least one change in behavior based on what they say. It doesn’t need to be the issue they were most concerned about, just an issue. Over time, people will see that you’re listening and changing, and will open up more (guaranteed).

- Ask people “On a scale of one to ten, one being God Awful and ten being Awesome, how would you say we’re doing right now.” And then once you have an average (let’s say 7)[7], ask folks for ideas on getting from a 7 to an 8. You’ll be amazed what will show up as suggestions, and how you’ll quickly be able to figure out major issues of discomfort for a person or a team.

- Don’t ask if everything is OK; ask what could be better. The question “does anyone have any issues they’d like to bring up” will rarely get sensitive issues like “you’re not involving me enough in the project” on the table. On the other hand, the question “hey guys, any thoughts on things we could do to make life more enjoyable for folks on the project” (assuming it’s asked openly and honestly) will often bring up suggestions like “it’d be great if I could consulted the next time we have to change the user interface, because I could help you with …”.

- Everything else failing, it can sometimes be useful to have a 3rd party ask or survey for the feedback, with a guarantee that you’ll only get a summary of everyone’s feedback without identifying someone. That said, while this is what most managers of large teams or client organizations end up doing, I think it’s the least successful way to get good feedback (but you at least get some).

How I Use SOAP

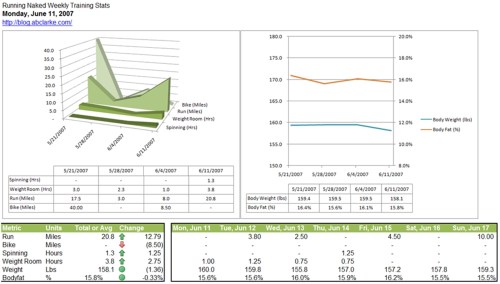

For changing things about myself (to which, to be honest, I’m fairly emotionally attached), I tend to be more subjective than objective. I often feel like I’ve worked out harder than I actually have. I feel like I’ve eaten less than I actually have. And so, I’ve tried over the past few years to bring more objective data to bear. When trying to lose weight, I now track what I’m eating and measure it (in addition to weight). I use a heart rate monitor to figure out how hard I’m actually working. Sometimes I don’t like seeing the data (this week, my body fat is up…), but it helps me figure out how to keep things moving in the direction I want.

In business settings, I’m the opposite, and tend to like numbers too much. So, I try to step out of a spreadsheet and ask for opinions. A former colleague of mine and I used to swap stories every 2 weeks about how we both would “walk the floor” for a couple of hours each week, just so we could chat and get a sense for mood.

But mostly, I try to constantly remind myself that every problem can be viewed in two ways: with numbers, and with stories.

[1]Now to be fair, in case anyone can guess who “S” is, S is one of the cleanest folks I know. He may wear sweaters a little too much, but otherwise has impeccable personal grooming habits.

[2]They also form a differential diagnosis, which is also useful to look at as a manager, but I’m not going to go into that here.

[3] I tend to tweak in this direction.

[4] An example of this is most parents report that their children are of “above average” intelligence, despite the fact that objectively this is unlikely.

[5] Examples of how rational people can make bad decisions based on only objective data (and no subjective data) because of their emotional distance from the topic abound, but can often be seen in action (along with several other factors) in decisions large companies make leading up to major disasters. Usually quantifiable ROI will trump any subjective pleas for help. See Union Carbide’s decisions leading up to the Bhopal disaster for example.

[6] For those who hear this and think “my god, how could you not ask someone how they feel!!!”, congratulations. You’ve got the “S” down. Now, how good are you about measuring things objectively?

[7] If you track this number, it can be a fun measure of team’s morale throughout a project. Expect it to start high, go low in the middle, and go high at the end 🙂