(2 of 5 in the Pragmatic Path to Agnosticism)

Imagine a Faith that has delivered miracles you’ve actually seen in your lifetime, other miracles that can be conclusively documented in prior lives, and that promises, based on an unparalleled track record, continued miracles in the future.

Imagine you have just been admitted into the leading seminary of that Faith, where you, surrounded by true believers and acolytes, are promised a position in the clergy and a chance (however small) to brush arms with the saints of the Faith, and someday perhaps be a saint yourself.

Imagine all that is asked of you to be part of this world is hard work, and strict adherence to doctrine. Officially, you can even worship another God if you’d like. What’s not to like?

Do all this, and you’ve conceived of Caltech. I was admitted in 1992 , joined a fraternity-like dorm, and found a new way of viewing life that would shape my outlook on the world.

, joined a fraternity-like dorm, and found a new way of viewing life that would shape my outlook on the world.

It was here, after having rejected Catholicism in high-school, through using several of the new shiny tools and toys I was given during my education that I came to be a devout atheist.

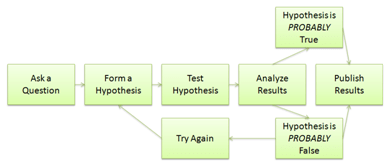

The Scientific Method

Science is founded on many principles, but few are more important than the Scientific Method. It’s a series of steps that are drilled into every budding scientist, and that you (should) follow throughout your career. You start by having a question you want to answer, such as “what does matter consist of” and then you go from there:

One of the key points in the method is how it determines truth or falsity. The method does not have to completely prove something – only show a hypothesis is consistent based on known data, is probably true, and can make some (falsifiable) prediction about the future.

If you can meet these three definitions, then your hypothesis achieves the coveted title of “accepted scientific theory.”

A Tangent on Probability

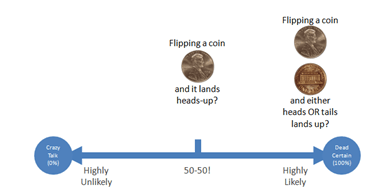

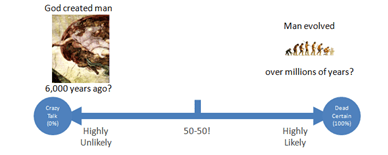

Many readers may be familiar with probability, but let’s go through a brief refresher. In science we talk of events occurring with a certain probability, and all we mean is, all things being equal, how LIKELY is the event to occur. Events can be very likely (i.e. more times than average, the event will occur) or very unlikely (i.e. more times than average, the event will not occur). Imagine placing an event along the following scale:

Now, this being science, folks like to apply numbers, and then usually assign probability a number between 0% and 100%. What does that mean? Well:

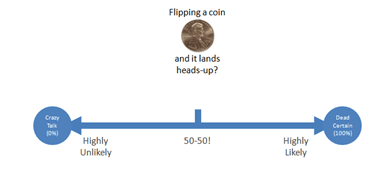

0% is “it will NEVER happen” and 100% is “it will ALWAYS happen”. And 50% means “it might or might not happen”, or “50-50”, or “even odds.” Let’s consider the classic case of “flipping a coin”:

On average, you’ll get heads once out of every two coin flips. So, the probability of getting a heads (assuming an average coin) is 50%. What about the odds of getting EITHER a heads or a tails?

If you’re asked to bet $1 to potentially win $2 on this question, it’s probably a good idea to take the bet. You’ll win ALMOST all the time. But you might think the probability of getting EITHER heads or tails would be 100% or “Dead Certain”, but it’s not. Why is that? Well…

…it’s possible that the coin will land EXACTLY on its side. The probability of this occurring is very very small, but it’s not zero. So you can’t say the odds of getting EITHER heads or tails is 100%, just that it’s very close (say, 99.9999%).

That is an important part of the scientific method. It tells us what is PROBABLY true, but it is usually impossible to prove anything to 100% (one exception). Still, being PROBABLY true is usually enough, and is very valuable: you can use it to make extremely accurate predictions about the future! For example, I confidently predict the sun will rise tomorrow, but technically the probability of that occurring is not 100%.

And I’d guess most people can agree on the likelihood of the following events being true and make some accurate predictions about the future based on them (for example, will you find a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow tomorrow?):

Technically as an Irish citizen I’m require to believe it is possible leprechauns exist, but I know it’s extremely improbable. It’s also possible that Lucky Charms Cereal does not actually exist (e.g. we all live in a Matrix like world), and I really hope it doesn’t, but it is extremely probable that it does exist.

March of the Scientists

Seems boring (it often is) but this method, in various forms, has been followed since the ancient Greeks, and the results have been outstanding. Think of the miracles that science has brought us, and almost all can be attributed to consistent repeated application of the scientific method: the theory of gravity, plastics, flight, nuclear power, and computers to just name a few. Consistent application of forming hypothesis, doing tests, examining data and repeating: in this way, we have uncovered the world.

And coincident with the rise of this method, a culture has arisen among scientists, and Caltech is no exception among them. It is a culture of intense optimism in the belief the science can continue its rapid progress and illuminate more of the universe. And it is a culture of intense skepticism, questioning those who believe in things that science has proven to be false but also (usually) relentlessly questioning the things that science has already proven to be true (a good example is how Einstein questioned Newtonian gravity and as a result brought a deeper understanding of that theory). (Note: in its purported focus on self-questioning, science is differentiated from almost all other faiths, and certainly all mono-theistic faiths I know of).

What does this have to do with God? I had struggled with the concept of God, and my struggles intensified as I learned more about the world. Even before I went to college, I had formed a belief that the world was divided into things we knew (could prove) and things that were unknown (we hadn’t yet proved or disproved), and I was trying to rapidly expand the former. God and the concept of spirituality firmly lived in the world of the Unknown for me.

Caltech showed me was a way to rapidly expand what we knew, gave me a set of tools that could be used to achieve that goal, and imbued me in a faith that we will continue to make progress.

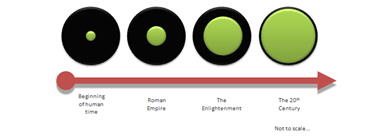

I viewed the world at the start of mankind as being mostly “The Unknown” with a small set of knowledge (e.g. how to make fire)…

…and that over time through the application of the scientific method we’ve rapidly expanded on the amount we know.

The more we looked for spirituality in the world of the known, the more we failed to find it, and we were rapidly running out of “unknown” areas where spirituality could hide. Evidence of the existence of God was scarce. In fact, the data and experiments done by mankind over the last 2,000 years, and especially since Darwin, have pointed towards the improbability of the existence of the God I grew up with (and certainly in the concept the world was built in 7 days 6,000 years ago).

I came to believe during my time in college that we were rapidly expanding on our knowledge and removing places for God and Spirituality to hide, and that we were likely to prove that concepts of God, spirituality, Plato’s unmoved mover, and others were nothing but the biochemical rantings and ravings of a fit species trying to survive:

Support Group for Atheists

And I wasn’t alone in this belief – in college a belief in the non-existence of God was the most popular view point among my compatriots (agnostics were tolerated, but theists were ostracized). I believe among hard-science intellectual communities today, it remains the dominant belief due to three arguments:

- There has been a relentless increase in the things we’ve proven about the universe.

- During thousands of experiments, we have found no evidence that proves the existence of God.

- The culture of science, correctly, puts huge value on skepticism.

Therefore, it is PROBABLE that God and spirituality are purely concepts, invented by man, and any instantiations of either concept can be wholly explained via (eventually) knowable physical phenomenon. And anyone who says anything different, well, that’s “crazy talk.”

And it’s fun. It leads to wonderfully amusing things like the God FAQ, cute summaries of traditional theist arguments for the existence of God, and countless fun spoofs of people of Faith including one of my favorite, What Would Jesus Drive?

I’m a sarcastic person, and the opportunity to use these tools and logic to eviscerate the concepts I’d had forced upon me as a young man was too good to give up. And I became an ardent hard-core atheist, mocking any who tried to advance an alternate view of existence.

(…by the way, hard-core atheists are not quite as amusing, as Unitarian Jihadists…)

What’s Your Problem?

So now I had a philosophy to replace my concepts of order in the universe. What was the problem? My friend Sarah put it to me much better than I ever could write, so I quote:

“There has been a philosophical gap there, maybe since Spinoza. I think atheists and agnostics need a spiritual outlook as much as anyone else, but they have more difficulty finding it. (By “spiritual” here, I am referring to a sense of wonder, awe, or inspiration, and obviously not a belief in supernatural agents.) I find people like Bertrand Russell inspirational in the sense that they lived good lives despite a lack of belief, but atheist philosophers have a tendency to recommend calm stoicism in the face of the universe, rather than inspiration or awe. Stoicism is nice and all, but it doesn’t get you through the day.”

I gradually realized that pure atheism without any sense of spirituality “didn’t get me through the day.”

And just as importantly, I realized that my logic in arriving at hard atheism, the 100% confident belief in the non existence of a spiritual element to the Universe, was (and is) horribly flawed.

Why? Strangely (and likely to the dismay of Creationists) Darwin and a German gentleman named Heisenberg point the way.

(which I’ll continue next week…)

– Art

Help me raise over $10,000 to help people suffering from cancer

Love the links. Reminds me of the blog of a mutual friend that I used to read religiously until he got a girlfriend and stopped doing updates. [I assume you know who I’m referring to but send me email offline if you’re uncertain]

Art, my boy, you’ve always been extremely articulate. And this is a great little write up, but these little pictures and diagrams leads me to believe:

1. You’ve been doing the dog and pony show too long

2. Jen’s been too busy at her doctorly duties and has been leaving you alone too long.

I’ll offer to your excellent analysis something else:

1) Your answers are only as good as your questions.

2) My opinion is that “science answers ‘how’, not ‘why'”. Philosophy/religion answers ‘why’. Understanding the difference between how and why (similar to the difference between tactics and strategy) is crucial to resolving this otherwise false dichotomy people like to make about the difference between science and religion.

for example, after getting beaten up pursuing a scientific career, i realized there is nothing in scientific training that answers, “why are you doing this” on a regular basis. it is your responsibility to refresh your own motivations. if you get burned out and run out of curiosity, you *have* to figure out a way to get that back if you want to keep being a successful scientist. because the moment that you lose that sense of wonder about exploring new ideas about physical reality, then it all turns to boring, difficult, meaningless equations, random phenomena and antisocial behaviour.

it is hard to stay engaged and connected. to lose that is like thinking Buddhism is just about non-attachment; it reduces to nihilism.

Hey Kujo,

Totally agree on all points.

Annie,

what… one power point too many?